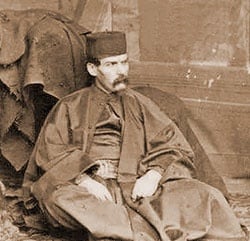

Who was the greatest traveller of the Victorian era? Amongst the usual top contenders you will find the name of Sir Richard Francis Burton. Best known for translating The Thousand and One Nights from Arabic and for visiting Mecca in 1853 disguised as a Muslim pilgrim, Burton wandered for years throughout the Middle East, Far East and Africa. He had an extraordinary talent for languages – he could speak twenty-nine of them – and was a master of assimilating himself into local cultures. Just after his death in 1890 he was described as ‘a Mohammedan among Mohammedans, a Mormon among Mormons, a Sufi among the Shazlis, and a Catholic among the Catholics.’

But for all Burton’s camel rides through the desert and exposure to different customs, he never shook off the racial prejudices of an upper-class Victorian gentleman. In an account of a trip to West Africa, he writes of the ‘pollution’ of Medeiran blood by ‘extensive miscegenation with the negro’. When he needs people to carry his luggage into the jungle, he buys himself some slaves without a second thought. Burton’s experiential adventuring failed to turn him into an empathist.

That is the problem with travel. There is no guarantee that it will result in an outrospective awakening in which you come to see the world through the eyes of others. Too often we venture abroad, guide books in hand, without learning much about the lives of the locals, who we stare at from the outside as if they were exotic animals behind a glass pane. This is precisely what occurs in the case of ‘poverty tourism’ today, where you might visit Soweto or Rio looking briefly at the slums from the comfort of an air-conditioned jeep.

My vote for the top Victorian traveller would not go to Richard Burton. Instead I would award it to Mary Kingsley, niece of the writer Charles Kingsley. Born in London in 1862, Kingsley received no formal education, yet by raiding her father’s library managed to teach herself chemistry, mechanics and ethnography. She also immersed herself in the memoirs of explorers, and in 1893, filled with enthusiasm for foreign travel, embarked on her first trip to West Africa.

She was a rare woman in a man’s world, travelling alone most of the time, climbing the mountain peak of Great Cameroon and canoeing down the rapids of the Ogowé River. She is remembered by ichthyologists for discovering three species of small fish, which are duly named after her, and for being one of the most intrepid early female explorers, happy to stare a leopard in the eye. ‘Being human, she must have been afraid of something,’ Rudyard Kipling wrote of her, ‘but one never found out what it was’. What made her truly remarkable, however, was her attitude to the so-called ‘African races’.

A notorious letter Kingsley wrote to the Spectator newspaper in 1895 began with the accepted Victorian belief that ‘the African races are inferior to the English, French, German, and Latin races’. But following this admission, she broke the taboos of her age by arguing that the natives were far from being immoral savages. ‘I have lived among and attempted to understand the Africans,’ she pointed out, and in mental and moral affairs ‘he has both a sense of justice and honour’, while ‘in rhetoric he excels, and for good temper and patience compares favourably with any set of human beings’. Africans are no more cruel than any other race, and although their funeral rites might appear strange, they are little different from those of the ancient Greeks. Unlike Burton, Kingsley was ahead of her time in realising there was no such thing as the ‘negro’, noting that ‘there is as much difference in the manners of life between say, an Ingalwa and a Bubi of Fernando Po, as there is between a Londoner and a Laplander’. While the gentlemen readers of the Spectator considered her views a shameless defence of barbarians and cannibals, she caused further uproar by comparing Africans favourably to Protestant missionaries, suggesting that the natives’ good qualities ‘are very easily eliminated by a course of Christian teaching’.

The example of Mary Kingsley suggests we should rethink the meaning of being an explorer. The greatest explorers have not been those who pushed back the geographic frontiers, but rather those who have travelled beyond the frontiers of their own prejudices and assumptions – whether those are based on race, class, gender, religion or some other category. A successful expedition is one which challenges and alters our worldview, liberating us from the narrowness of deeply ingrained beliefs that we have often unconsciously inherited from culture, education and family. Mary Kingsley’s experiences of travel did just this, exploding the racial prejudices about Africans that were the stuff of the Victorian drawing room.

Thomas Cook, a lay Baptist preacher who was the founder of package holidays in the nineteenth century, wrote that the ultimate purpose of travel was ‘to dispel the mists of fable and clear the mind of prejudice taught from babyhood, and facilitate perfectness of seeing eye to eye.’ Mary Kingsley succeeded in this endeavour. Richard Burton did not.

You can read Mary Kingsley’s letter to the Spectator here. Her views on race are discussed in Sven Lindqvist’s The Skull Measurer’s Mistake, a great book of mini biographies of historical figures who spoke out against racism.

Hello

I am a BBC documentary maker who is making a film on history of travel told through antiques. I would love to speak to Roman Krznaric. I can be called on 0207 907 3430 or simply just email me.

Many thanks

Jenny Dames

(Producer/Director)