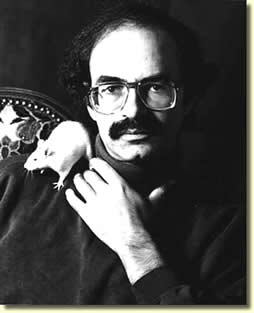

The history of outrospection is yet to be written. But when it is, you can bet the name of Peter Singer will be there. Singer is one of the world’s most influential moral philosophers, best known for his 1975 book Animal Liberation, which has become a foundational text of the animal liberation movement. But in the 1990s he also wrote another prescient book, How Are We To Live: Ethics in an Age of Self-Interest, which contains the kernels of an outrospective approach to thinking about the world.

How Are We To Live is essentially a critique of consumer society and the self-interest driving it, which argues that we are unlikely to find meaning in life by going shopping, and more likely to achieve a sense of fulfilment by committing ourselves to ethical living.

Central to his argument is understanding the damaging effects of what he calls ‘the inward turn’. This refers to the rise of an excessively introspective culture of psychotherapy which, he believes, has done precious little to help us achieve the good life.

When he moved to New York in the 1970s, Singer noticed how so many of his academic colleagues were in regular therapy. Many of them saw their therapist on a daily basis, and some were spending up to a quarter of their annual salaries sitting on their analyst’s couch. Singer found it strange that these people did not seem any more or less disturbed than his friends and workmates in Melbourne or Oxford. So he asked them why they were doing it. ‘They said that they felt repressed,’ remembered Singer, ‘or had unresolved psychological tensions, or found life meaningless.’

What he had recognised was a significant shift in therapy culture which has been taking place since the 1970s. Instead of focusing on treating those with mental illnesses, therapists were now also there to help people find meaning in their lives. As M. Scott Peck once put it, therapy is a ‘short cut to personal growth’.

The problem, writes Singer, is that you are unlikely to find meaning and purpose by looking inwards:

‘People spend years in psychoanalysis, often quite fruitlessly, because psychoanalysts are schooled in Freudian dogma that teaches them to locate problems within the patient’s own unconscious states, and to try to resolve these problems by introspection. Thus patients are directed to look inwards when they should really be looking outwards… Obsession with the self has been the characteristic psychological error of the generations of the seventies and eighties. I do not not deny that problems of the self are vitally important; the error consists in seeking answers to those problems by focusing on the self.’

Moreover, therapy culture is decidedly lacking in ethical content. He disapprovingly quotes a Gestalt therapist who writes how the nature of morality is changed by the therapeutic process:

‘The question ”Is this right or wrong?” becomes ”Is this going to work for me now?” Individuals must answer in the light of their own wants.’

It may be that Singer is too simplistic in his depiction of psychoanalysis, and too harsh in his critique of its usefulness. But he was one of the first thinkers to see that we may not have the balance right. It could be that we need more of an outward turn – a healthy dose of outrospection – if we are going to discover what we should be doing with our lives.

But what would turning outwards mean in practice? Singer has an answer. He thinks we would be best off by dedicating our lives to pursuing a ‘transcendent cause’. This refers to committing yourself to some cause or project that is ‘larger than the self’. At this point he turns to support from the psychotherapist Victor Frankl, who ‘is exceptional in his insistence on the need to find meaning outside the self’. Frankl’s most renowned work, Man’s Search For Meaning, documents his time as a prisoner in Nazi death camps, where he saw that those who were most likely to survive were not those who were physically strongest or best at scavenging food, but those who felt they had something to live for in the future. Perhaps it was to be reunited with their son, or to finish writing a scientific textbook which they had started before the war. Frankl quotes Nietzsche: ‘He who has a why to live for, can bear with almost any how.’

Of course, there are many forms of transcendent cause. Supporting one’s Mafia family is a cause larger than the self, as is being a member of a religious cult. For Singer, the kinds of transcendent cause that really offer lasting fulfilment are ethical ones. Committing yourself to animal liberation, human rights, ecological activism or some other issue of social or planetary justice is going to be more sustaining than committing yourself to a football club or a corporation. Thinking back to his academic colleagues, he had this to say:

‘If these able, affluent New Yorkers had only got off their analyst’s couches, stopped thinking about their own problems, and gone out to do something about the real problems faced by less fortunate people in Bangladesh or Ethiopia – or even in Manhattan, a few subway stops north – they would have forgotten their own problems and maybe made the world a better place as well.’

A pretty damning judgement. But then again, Singer has never shied away from speaking his mind.

Brilliant piece, Roman!

There is another element of Singer’s attack on the psychotherapy culture worth highlighting: it sees the roots of problems as not only individual, but historic. Psychotherapists typically look for solutions to things that happened in the past – eg ‘my mummy didn’t love me enough’. Hence, shrinks typically turn our gaze not only inwards, but also backwards in time. Since the past cannot be changed, only our understanding of it, it means shrinks tend to generate a powerlessness – contrary to what many of them claim to offer. And trying to change our perceptions or memories of our history is a much poorer form of empowerment than addressing the real problems of now.

It’s a powerful insight: therapy and political action might be alternatives. But does Singer prefer the right one? What about the dangers of political action that substitutes for therapy? Do we really want people who feel themselves in need of therapy to shape our world without getting personal help? If they don’t know themselves, Singer implies, all the better to know the world and act to ameliorate it.

Perhaps the larger question is why introspection and politics/activism came to be, in the 1970s, alternative methods of pursuing personal fulfillment — from which point of view they look less like opposites than parts of a common phenomenon.

I may be completely wrong, but his perspective seems awfully reductionist. That he can be so dismissive of psychotherapy as a whole makes me think he’s never had some issue that needs treating.

As for service being some kind of panacea, I’m reminded of something C.S. Lewis once said:

What one person finds to be “moral,” particularly when it’s used as a crutch, can be quite dangerous for those nearby. Moreover, is it a good idea to encourage a kind of selfish philanthropy? I have to imagine this will lead to an awfully lazy kind of “good deeds,” the kind that look profound but ultimately accomplish little.

Having experienced both being in therapy and helping others, I would agree the latter is ultimately more fulfilling. To those who think you shouldn’t do good to feel good about yourself, grow up. That’s the way humans are. If as human beings we are programmed to act in self interest, we might as well enrich ourselves through good works rather than hedonism.

Yes, it is time to get off the analyst’s couch, and to start focusing on the external sources of the problem, and solutions.

From what I see, as someone who’s focused on developmental psychology/philosophy, the underlying problem is that most people have very unhealthy lives (physically, emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually) while simultaneously being convinced by the outside world that they have everything they need to be healthy and have no right to complain or be sick. So, effectively, their Id knows one reality while the superego is claiming to know an entirely different reality. So people either have to reject society and respect themselves, or reject themselves by accepting society. Either option makes it impossible to healthfully grow and fit into their environment.

Only when we, as a society, make it clear that the human world is NOT healthy at all, and DOESN’T provide us humans with what we need to be honestly healthy very often, will we even have a chance to heal. This is the reason that focusing on an environmental~social cause helps us, because it’s at least allowing us to believe that the way things have been going weren’t supporting everyone’s health the way we need them to. With this awareness, even if we still are deficient in many ways, and are still bombarded with toxic crap, we at least know that there is a reason we are sick, so that we feel free to reject and vent that toxic stuff when it shows up, rather than thinking that there is something “wrong” with us for wanting better quality stuff in life, and for not wanting to have to deal with the crap that society tells us is “good for you!”.

Very interesting. And also surprising. Peter Singer is a powerful thinker, but it seems to me that one of his strengths/weaknesses is his tendency to ignore other people’s experiences. I would suggest that if you are someone who doesn’t feel the need for counselling or therapy and have never experienced any benefit from it, then the chances are you’ll dismiss it as useless. In fact, there are plenty of examples of people who feel therapy has helped them to understand themselves better. I’m certainly one of them.

I’m not looking for meaning in life and I’ve certainly no desire to focus on my own problems – to be honest I find them a bit boring and I’m tired of them. But I genuinely struggle in my relationships with other people – particularly close relationships – and I’ve found therapy has helped me to work out some of the stuff that is going on in my head and understand why it can lead to challenging behaviour on my part.

Therapy has helped me understand why I get scared and why I get angry (the two are linked and, yes, I was helped by looking at experiences in early childhood and family relationships). It’s helped me to form and maintain better relationships and it’s helped me to empathise better with other people and understand the roots of challenging behaviour.

So, crucially, therapy has helped me mature emotionally. I am now in a position to give energy and time to others, which I do whenever the opportunity arises. The two approaches to contentment aren’t mutually exclusive – if you don’t feel you are functioning very well has a human being then you can look inwards to find out why that might be, and also combine that with working for others and forming meaningful, mutually beneficial relationships.

Well, it was really an interesting post. In my view if you are someone who doesn’t feel the need for counselling and therapy and have never get any benefit from it, then the more chances that it will be useless.