For over half a millennia Christian art has attempted to use empathy to help people understand the reality and significance of Christ’s suffering on the cross. We are offered paintings and sculptures showing nails piercing flesh, gaping wounds and seeping blood that aim to have us not only see what Christ endured, but also to physically feel his bodily pain. As the art historian Jill Bennett points out in her book Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma and Contemporary Art:

‘The images developed from the late medieval period with the express function of inspiring devotion were not simply the “Bible of the unlettered” in the sense of translating words into images. Rather, they conveyed the essence of Christ’s sacrifice, the meaning of suffering, by promoting and facilitating an empathetic imitation of Christ.’

The idea of the imitation of Christ’s suffering had its most memorable form in the practice of flagellation which emerged in thirteenth-century Europe. This involved methodically flogging or whipping your own body using specialised implements such as rods, switches and cat-o-nine-tales, in the hope that you were experiencing the pain that Christ went through and were therefore bringing yourself closer into communion with him. Flagellation took off in the mid-fourteenth century during the Black Death. The plague was believed by many Christians to express the wrath of an angry God, and the rather sadomasochistic activity of flagellation was considered an effective way of appeasing him through a form of self-punishment.

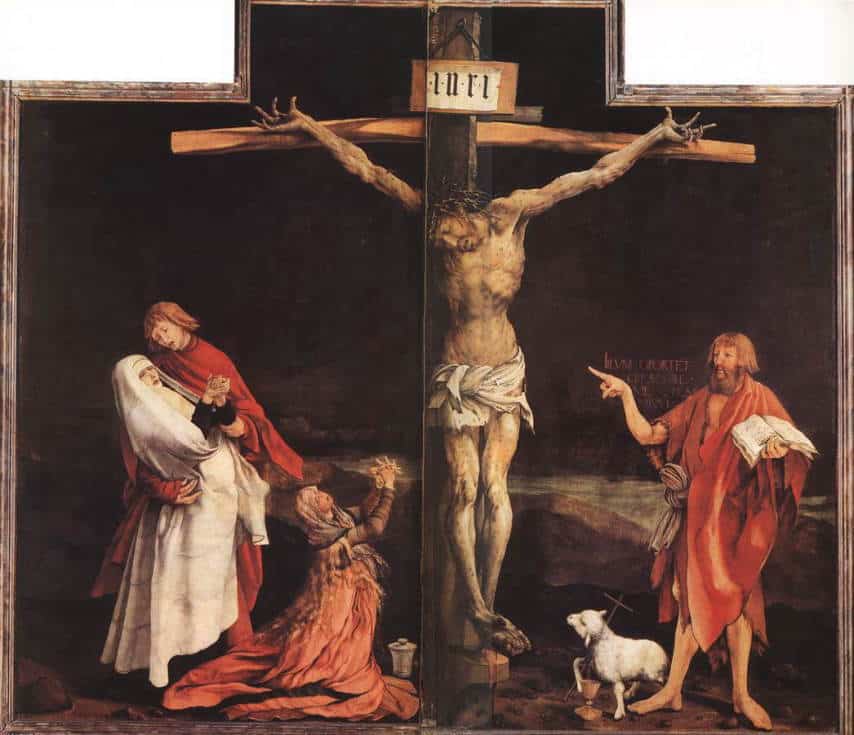

Standing before a painting or sculpture of the crucifixion can only be an empathetic second best to a serious session of flagellant self-harm. So just how successful has Christian art been at creating an empathetic response in the viewer? Early depictions of the crucifixion were quite genteel, and did little to convey the suffering involved. But in the sixteenth century artistic depictions became far more gory. The classic example may be the German artist Matthias Grünewald’s ‘Crucifixion’ from 1515, the central panel on the Isenheim altarpiece. The upturned fingers at the end of Christ’s torturously extended arms makes the experience look genuinely painful. It is as if he has been stretched out on an inquisitor’s rack before being nailed to the cross.

The current exhibition at the National Gallery in London, The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting & Sculpture 1600-1700, offers several works that rival Grünewald’s effort to arouse our empathy. The most successful, in my view, is Gregorio Fernández’s painted wood sculpture ‘Dead Christ’ (c.1630). Christ has been taken off the cross and is lying completely naked apart from a loincloth. The corpse is still unwashed and awaiting burial. His half-lidded eyes look absolutely dead, his head tipped to the side like a car-accident victim. My own eyes were drawn to the blood – drooling from his gaping mouth, pouring out of the gash below his right nipple, caked on his knees and left shoulder. And then there were the gruesome holes in the feet and hands where the nails had been extracted.

I tend not to have a strong bodily empathetic reaction to these visual representations of Christ’s suffering (although I do occasionally get a few goose bumps). This may partly be because I don’t have the appropriate religious beliefs that might connect me to what I’m looking at. But it is also because the works do not draw me far enough into Christ’s perspective on the event – I can see what is happening to him but don’t feel I am really looking through his eyes or have entered into his skin. I remain outside the event as a spectator.

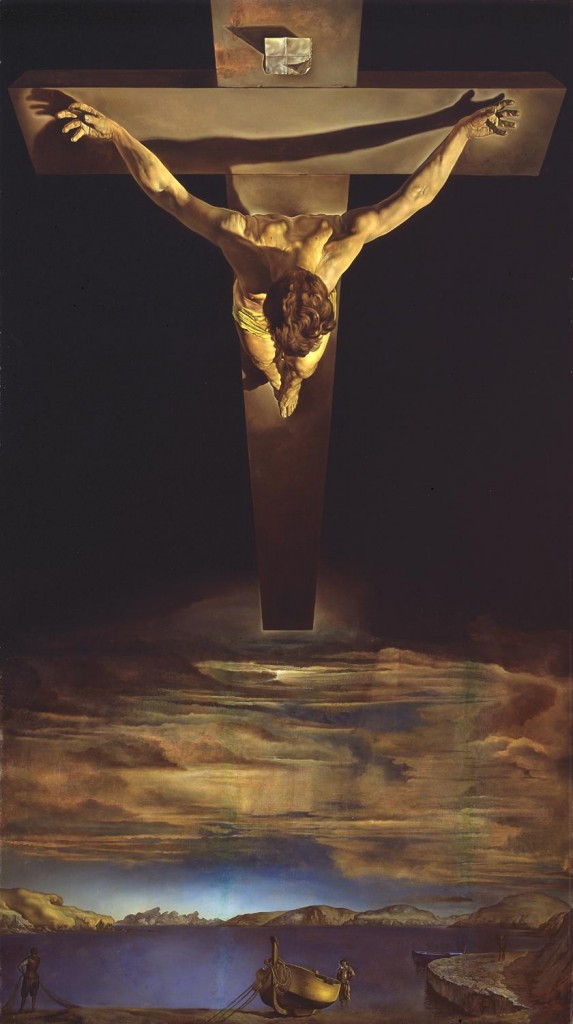

The one work that catapults me into Christ’s experience is Salvador Dali’s 1951 painting of the crucifixion, known as ‘Christ of Saint John of the Cross’. Although devoid of nails, blood or crown of thorns, by lifting me to the heights of Christ’s perspective, it has a greater empathetic effect than even the most blood-strewn of the Spanish works at the National Gallery.

I do, however, recommend a visit to the exhibition. Perhaps the artworks will make your body twitch more than mine, and give you a tiny taste of the realities of flagellation.