The following article originally appeared in The Guardian.

The following article originally appeared in The Guardian.

The great tragedy of modern parenting is that we’ve forgotten its history – and mothers are paying the price. Contrary to popular belief, the superdad who takes on a serious share of childcare and housework is not a new invention. Before the industrial revolution – a mere couple of hundred years ago – most men were stay-at-home fathers, skilled at comforting wailing babes and bathing squirming toddlers. I didn’t know this four years ago when my partner, Kate, became pregnant with twins. I had never wanted to have children, worrying that it would scupper my hopes of becoming a writer, so I panicked. How was I going to embrace the seismic shock of double-dose fatherhood?

The easy option would have been to play the typical bloke and let Kate – who has her own career – do most of the work. In British families where both parents work full-time, women still spend one-third more hours than men on household duties. Once they get home from the office, most mothers face a “second shift” in the home. The resulting strains are regularly vented in discussion forums on the internet. This recent post on Mumsnet received scores of sympathetic responses: “It has just dawned on me that my husband has absolutely no idea how hard I work looking after three kids under four whilst running my own business. I want to punch the useless twat!”

In my pre-dad days, I never really considered the gender imbalances and simply assumed it was the natural way of things for mothers to take command in the home, as they were the ones with all the maternal equipment and instinct. It was an unthinking view, even though my own father had taken full charge of parenting duties after my mother’s death from breast cancer when I was 10. He was the one who cooked supper for me and my sister every evening and vacuumed the house on Saturday mornings.

Seeking reassurance for my imminent life of fatherhood, while sweating in anticipation of the birth, I began reading parenting manuals. Few were written with men in mind. So I followed my bookworm instincts and began exploring parenting in the past and in other cultures. There I discovered how wrong I had been.

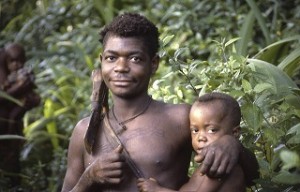

My prejudices started to crack when I stumbled across the Aka Pymies. Living in the jungles of the western Congo basin, Aka men are the world’s most dedicated dads. For 47% of each day they are either holding their children or are within arm’s reach of them. It’s the Aka man who will calm his crying infant in the night, even offering a gentle suck on his nipple (no, I have not tried this myself).

According to the anthropologist (and father of seven) Barry Hewlett, who spent two decades studying the Aka, the high level of paternal involvement may be due to the nature of their traditional subsistence activity, the net hunt. Men and women take part in this seasonal venture to trap small animals, and the babies come too, with men having the main responsibility for carrying them over the long distances covered. The more childcare Aka men do, says Hewlett, the more attached they become to their kids. Once they start, they don’t want to stop.

Yes, I know the Aka are an extreme case, but they are not alone. When Europeans first arrived in Tahiti in the 18th century, they were shocked to find that women could become chiefs while men routinely cooked and looked after children. In around one in four traditional cultures studied by anthropologists, men have played a major parental role. That still leaves a clear majority of societies in which women bear most of the childcare burden – indeed, in a third of cultures men barely lift a finger to help. The point, though, is to recognise the wide variety of parenting set-ups across human societies.

With the Aka on my mind, my assumption that childrearing was an essentially female occupation was now looking embarrassingly flimsy. But I could still tell myself that their culture wasn’t mine. Turning to European history, however, only challenged me further. We have not always been so different from the Aka as we might imagine.

The first clue lies in language. In the late Middle Ages, a husband was a man whose work, like a housewife’s, took place in and around the home: “hus” is the old spelling of “house” and “band” concerns his bond to the house that he rented or owned. One of his main tasks was farm work – and that’s husbandry, a term still used today.

This is revealing of pre-industrial society because, in rural areas especially, family life and working life were based in the home. Running the household was a joint enterprise: while a wife rocked the baby, her husband built the cradle and cut hay for the child to lie on.

As men were around the house much more, it’s not surprising that they often took on a big child-rearing role. A traveller visiting an English village in 1795 recorded: “In the long winter evenings the husband cobbles shoes, mends the family clothes and attends the children while the wife spins.” No slumping in front of the telly for an evening of Top Gear back then. Likewise, in the United States in the 17th and 18th centuries, says the historian Mary Frances Berry, “Fathers had primary responsibility for childcare beyond the early nursing period.”

Men were also thrust into single parenthood because so many mothers died in childbirth. Today one in 12 single-parent households in Britain is headed by men, but between 1600 and 1800, it was one in four. While men might remarry or employ domestic servants if they had the means, some one-third of single fathers during this period had no live-in support from other adults.

Men were also thrust into single parenthood because so many mothers died in childbirth. Today one in 12 single-parent households in Britain is headed by men, but between 1600 and 1800, it was one in four. While men might remarry or employ domestic servants if they had the means, some one-third of single fathers during this period had no live-in support from other adults.

Let’s not pretend that pre-industrial man was a domestic goddess. Women were typically still at the heart of the home and frequently couldn’t drag their men out of the ale house. But the modern hands-on father clearly has his predecessors.

The intriguing question is how we ended up today with women bearing the brunt of the housework and childcare. The standard explanation is patriarchy: that during the industrial revolution, between 1750 and 1900, men exerted their power by taking most of the new factory jobs, leaving women indoors to boil soiled nappies.

But that is too quick and not quite the whole of it. The truth is also that men were deskilled by industrial technology. With the invention of the enclosed iron stove in the 18th century, for instance, men no longer had to spend as much time at home chopping firewood. Then when coal replaced wood as fuel, they had to go out and earn cash to buy it instead. Men’s other traditional household crafts such as making shoes, tools and furniture were taken over by machines – but there were no clever gadgets invented to nurse a sick child. So by the 20th century, women were left holding the baby while men walked through the factory gates. Men’s long-standing role in the household had become a distant memory.

Nobody is taught this history at school. But when I discovered it, one of the most powerful myths of our time exploded before my eyes. Despite decades of women’s liberation, it is still widely seen as “natural” for women to be in charge of the home, while men charge off to the office. History has forced me to admit that, while women might breastfeed, there is no special female gene for sterilising bottles or cleaning the bathroom.

This is what inspired me to join the proud – if forgotten – tradition of the househusband. When our girl-boy twins, Siri and Casimir, were born, I stopped work for three months to look after them full-time with Kate (easy enough in countries like Sweden with 12 months of paternity leave; harder in Britain where the law is less generous). Now we both work a four-day week and split the household chores and childcare. Neither of us relishes changing nappies or endlessly peeling raisins off the kitchen floor, but I have accepted the realities of shared parenting as an important part of my life and who I want to be. Making pizza with my kids for lunch each Wednesday is a ritual I cherish – despite the sticky fingers and clouds of flour – and I love taking them to frolic at their playgroup, even if there are only one or two other men in the room.

I’m surprised by how much becoming a father has remoulded my character. I’ve become far more emotionally sensitive – I feel sorrows more deeply but also joys more strongly, a change for which I am grateful. It is as if my emotional range has increased from a meagre octave to a full keyboard of human feelings. That’s a pretty good argument for getting stuck in as a dad.

It certainly helps that my office is at the top of the house. In fact, history is coming full circle thanks to broadband and flexible working, which are bringing many men’s working lives back into the home in a way that has not been seen for nearly three centuries. That gives a growing number of fathers like myself the opportunity – and the obligation – to get more involved in their children’s lives, whether it’s making packed lunches or taking them for their annual jabs. We’re getting more medieval every day, and that’s a good thing.

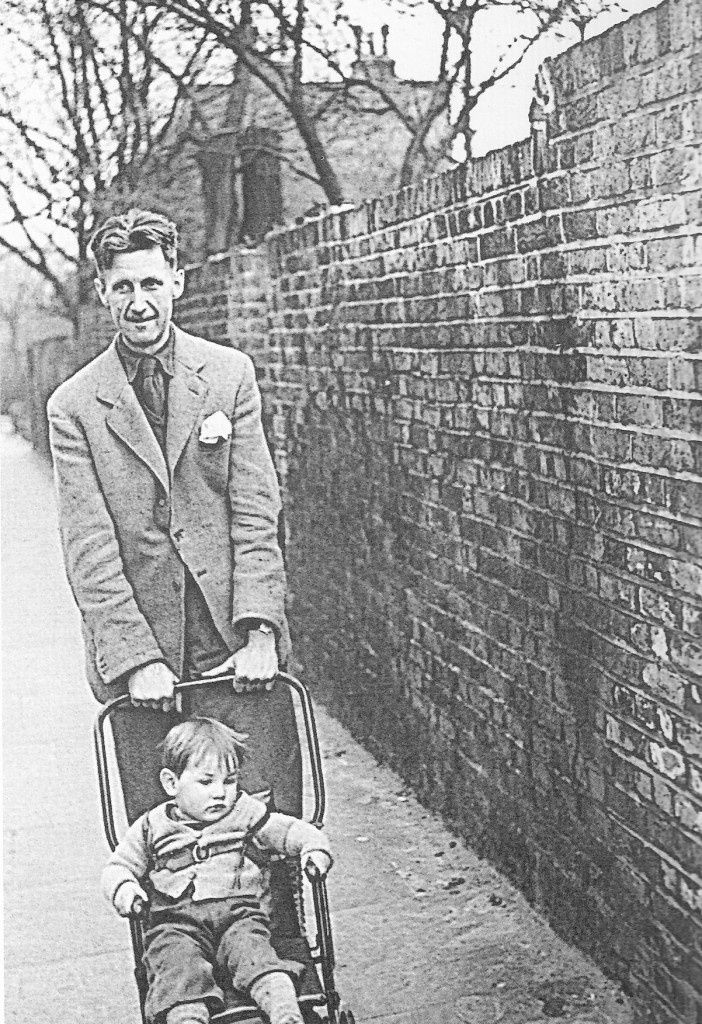

One of my most unexpected delights is that I have found new personal heroes: my favourite writers who also managed to be engaged dads. I can picture George Orwell rising at dawn to knock out an essay on his Remington typewriter, then wheeling his son Richard in a pram through the streets of postwar north London. Then there’s JG Ballard, who raised his three children after his wife died suddenly in 1964. After making breakfast and dropping them off at school, he would sit down at his desk at 9am to start writing, with his first whisky of the day as company. “Some fathers make good mothers, and I hope I was one of them,” he wrote.

One of my most unexpected delights is that I have found new personal heroes: my favourite writers who also managed to be engaged dads. I can picture George Orwell rising at dawn to knock out an essay on his Remington typewriter, then wheeling his son Richard in a pram through the streets of postwar north London. Then there’s JG Ballard, who raised his three children after his wife died suddenly in 1964. After making breakfast and dropping them off at school, he would sit down at his desk at 9am to start writing, with his first whisky of the day as company. “Some fathers make good mothers, and I hope I was one of them,” he wrote.

If they could do it, I should at least try. Of course, I am still torn between my family duties and career aspirations. But I’m learning, slowly, to become the father I never wanted to be.

This article originally appeared in The Guardian © 2012. It is based on my new book The Wonderbox: Curious Histories of How to Live.

Am loving reading your book! Wish you a joyful fatherhood.

Hi Roman,

Fascinating article. I came to the same conclusions about fatherhood and shared parenting after living in remote areas of Thailand and certain parts of rural France. In both places I found parenting was based on shared ability rather male/female. So if the wife was better with a saw and the husband the pot that’s what they focused on, working to their combined strengths not some idealised notion of male/female roles. And here’s the kicker most couples were good at everything they did, they weren’t divided and worked as effective teams.

Cheers, F